WRITING OF: Proriger

A little bit of behind-the-scenes info about my latest short horror story, Proriger.

Howdy! This is just a short little behind-the-scenes essay about my latest short story, Proriger- here I’ll cover the research, inspirations, the cover art, writing process, and a bunch of other stuff that went into writing this. Obviously spoilers abound, so if you haven’t read the story already you can do so below:

Inspirations

As stated in the postscript, the primary source that kicked off my creative drive to write this story was an episode of Dead Rabbit Radio- Episode 419- The Pensacola Monster Needs Human Flesh!

I do briefly want to note that I cannot overstate how inspirational Dead Rabbit Radio has been to me as a writer. Not only are the stories he covers- all true or at least allegedly true paranormal, conspiracy, and true crime accounts- very inspirational in their own right, but the host himself is just a great guy and very supportive of his audience in all our own creative endeavors. I highly encourage you to listen to the show, and I have a lot more of my own stories coming out soon that were inspired by stuff he has covered. If you enjoy my writing, you by extension enjoy Dead Rabbit Radio.

In Episode 419, Dead Rabbit recounts the story of Edward Brian McCleary, who told of how he and his four friends went out snorkeling one night in 1962 at the wreck of the USS Massachusetts, a battleship that was scuttled outside of Pensacola Harbor and was still largely abovewater when the story took place. A thick fog rolled in over the area as Edward and his friends swam around exploring the wreck, and soon they saw a large object shaped like a streetlight coming out of the fog towards them. This “streetlight” was revealed to be the long neck and head of a sea monster, which proceeded to devour Edward’s friends one by one as they frantically tried to swim to the wreck, where they had at least a small hope of safety. Edward was the only one who made it, clinging to the ship’s tall mast until morning, when he was rescued by a passing ship.

This short, evocative tale is what gave me the idea to try writing my own version of such an incident. The obvious difference is that while Edward Brian McCleary’s story is allegedly true, my story is pure fiction and makes no claim otherwise.

Now, because Edward’s account is so fantastical, I did look a bit more into it… even detached from my own story’s research purposes, I wanted to know if it was true. If there really are sea monsters lurking around an old battleship in Pensacola Harbor, I want to know so I can make sure to never go swimming there- or anywhere, ever again!

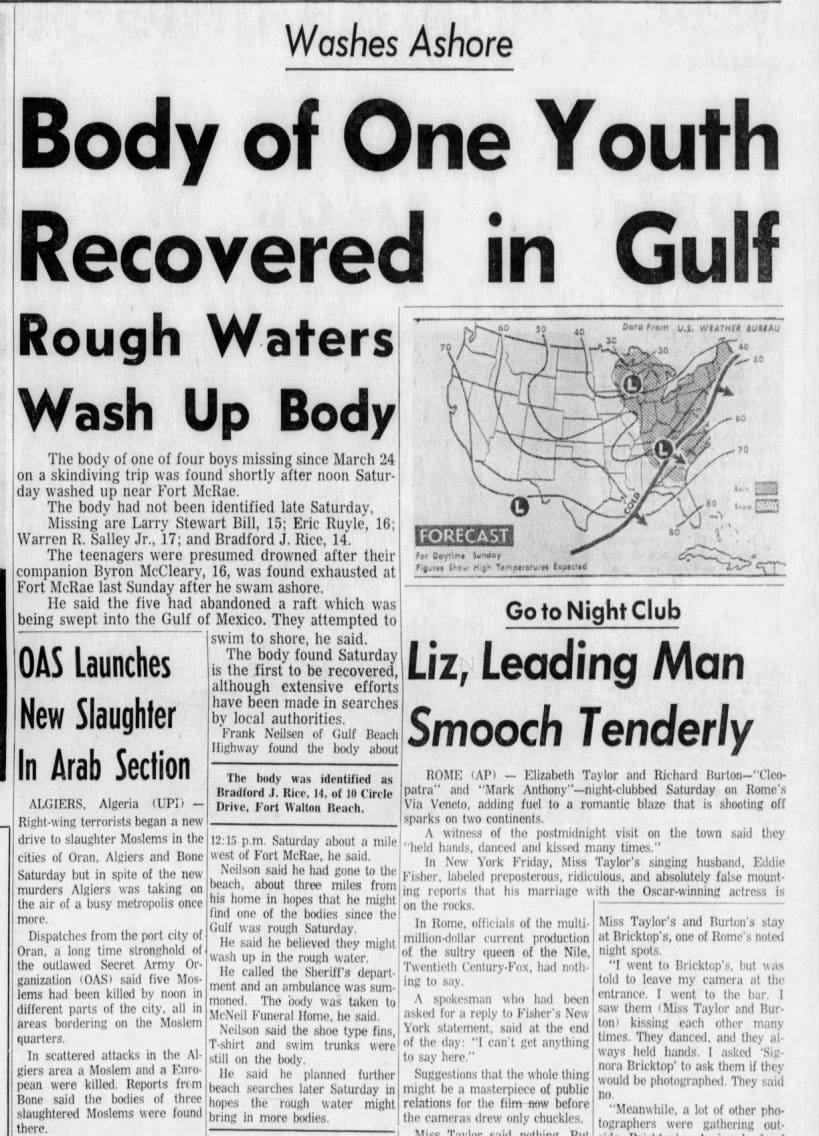

To my surprise, it turns out… it is mostly true! Edward Brian McCleary did exist, and he really was the lone survivor of a horrible accident that occurred near the wreck of the USS Massachusetts in March 1962.

The difference in the contemporary newspaper accounts is… there is absolutely no mention of a sea monster. Edward states that his friends all drowned in heavy seas after a ripcurrent pulled them away from the wreck. One of their bodies later washed up and the cause of death was confirmed to be drowning.

This raises some questions about the origin of the sea monster tale, which was first published in the paranormal-centric Fate Magazine in May 1965. The only three options I can think of are, in order of descending plausibility:

Someone saw Edward’s story in the newspaper and got the idea “what if they were attacked by a sea monster?” and then wrote and submitted a fictionalized account to Fate Magazine under Edward’s name (poor taste)

Edward himself fictionalized the real-life deaths of his friends and submitted it to Fate Magazine as if it were true (poor taste, Edward, poor taste…)

Edward Brian McCleary really was the lone survivor of a sea monster attack, it was officially reported that his friends drowned (meaning either Edward lied to the authorities, or the authorities covered it up), and he later told the true story to Fate Magazine.

Make of that what you will- this was all just a brief and interesting aside to my overall research for the story.

Before I get into the creature that actually features in the story, I would be remiss not to mention two other sources of inspiration for this story- Jaws, and a Stephen King short story called The Raft.

Jaws needs no introduction, everyone’s seen it. Overall it wasn’t that influential to the story’s development; its main contribution to my creative process was the more gradual reveal of the creature to the characters, mirroring how the scariest part of Jaws is how little we really see of the shark. Obviously we do eventually get lavish descriptions of what exactly the creature looks like, but until Jack is killed it is only revealed in bits and pieces- the tail, the head, some idea of the overall length of the creature. It isn’t until it breaches that we get a long description of its appearance, confirming to a knowledgeable-enough reader what type of animal it really is.

The Raft was a great little horror story with a similar setup to Proriger- four college friends go on a trip to a lake, swim out to a platform in the middle of the lake, and are attacked and killed one by one by an intelligent nonhuman adversary which prevents them from escaping back to shore. In The Raft, however, the creature hunting them is some sort of black gooey mass that looks like an oil slick; it hypnotizes its victims into touching it with colorful pulsations of its surface, then kills them by agonizingly melting their flesh. It’s also an unnervingly intelligent creature, which pulses up between the cracks in the wooden platform the characters are stuck on to get them. This intelligence was especially inspirational to Proriger.

At its core, Proriger is a love letter to all of the great horror fiction which has been written about Mesozoic marine reptiles, cryptozoological reports of late-surviving marine reptiles in the lakes and seas of the world, and the marine reptiles themselves.

I won’t look at the cryptids too extensively here, because… there are so damn many of them. I was inspired by them as a whole class more than any individual creature. The Loch Ness Monster, Ogopogo, Cadborosaurus, Morgawr, Champ, the Gloucester Sea Serpent, the U-28 creature, the submarine Alvin sighting, the Zuiyo Maru carcass… these and literally hundreds of others have been reported from large bodies of water the world over. I don’t know if they are really late survivors from the Mesozoic; I lean heavily towards “no”, but… I don’t know, maybe they are. People are definitely seeing something, even if- as in the case of the Zuiyo Maru carcass- it has a more commonplace explanation.

Regardless of whether or not great reptiles still ply the waterways of the world, the idea of it is extremely evocative and the enduring popularity of such legends is completely understandable. Proriger leans heavily into this cryptozoological element, being written as if it were a true account of such a sighting- albeit one far more dramatic that what is usually reported of lake and sea monsters- and employs the “late-survivor” trope outright at the end.

Cryptozoological reports and fictional depictions of the Mesozoic marine reptiles both tend to revolve around the justly famous plesiosaurs- those long-necked marine reptiles that lived alongside the dinosaurs1. These amazing creatures plied the oceans of the world millions of years before whales or dolphins were a thought in God’s mind, and they’ve been a staple of paleo-media ever since their discovery.

There are far too many examples to list- Journey to the Center of the Earth might be the earliest and most enduringly famous depiction; The X-Files had an episode about a late-surviving plesiosaur living in a lake; the found-footage show Lost Tapes had a bone-chilling episode about a giant maneating plesiosaur in Monterey Bay; Scooby Doo went toe-to-toe with Nessie at one point; the charming 1996 film Loch Ness featured plesiosaurs in the role of the famous lake monster2… etc. etc.

The depiction that was most influential to this story, though, was the party boat scenes from Harry Adam Knight’s book Carnosaur. In this book, the eccentric, misanthropic lord Darren Penward brings dinosaurs back to life via genetic engineering at his secluded English estate. Naturally, the dinosaurs break out of containment and kill a bunch of people, which the protagonists have to deal with3. One of the prehistoric beasts Penward clones is a plesiosaur, which escapes its huge containment pool, waddles like a seal into a nearby river, and rams a boat full of college kids aground. It then proceeds to pick off the drunk students one by one throughout the night as they try to get back to shore. That whole sequence is chillingly effective, and part of my mission with Proriger was to, in a very loving way, attempt to outdo it on the terror-scale. Whether or not I succeeded at this task is of course for you to decide. All I know is I had a BALL writing it.

On Mosasaurs

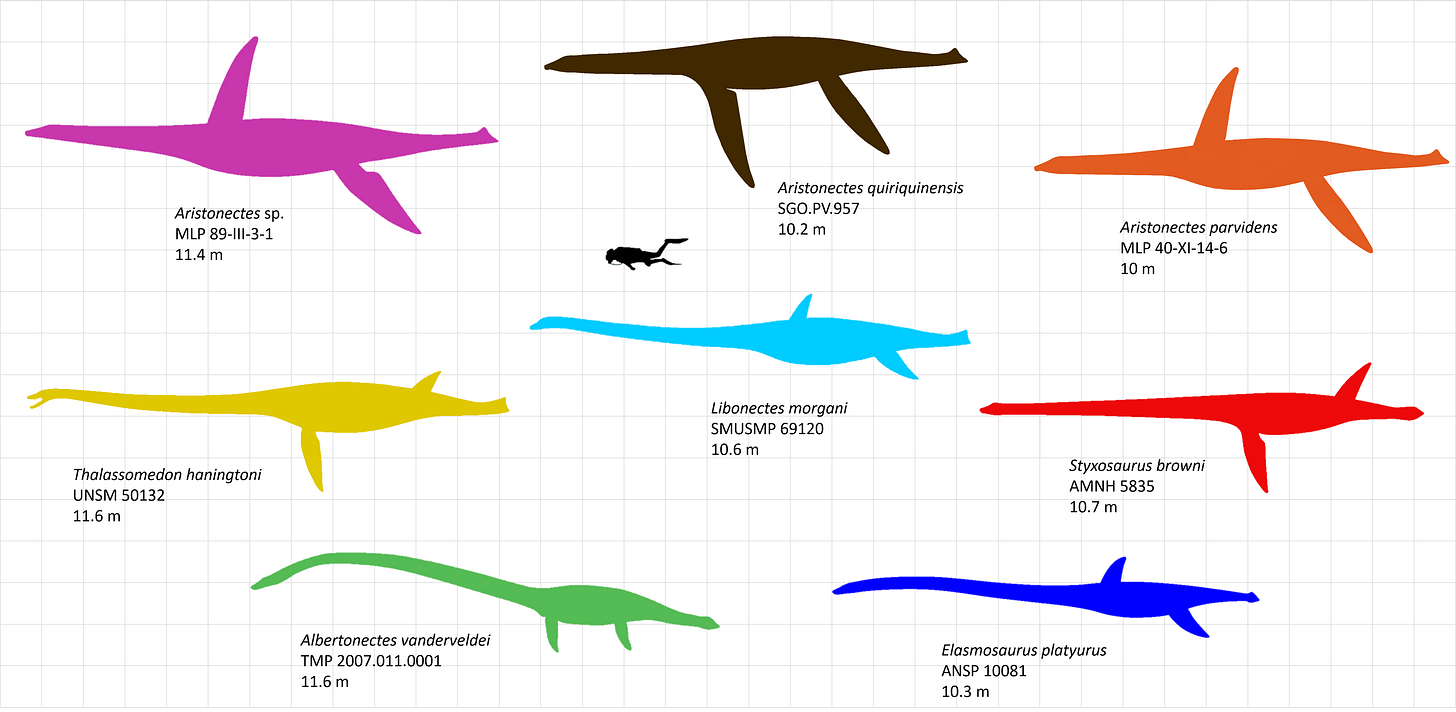

One stark difference between Proriger and its inspirations is that the creature in my story is not a plesiosaur. Rather, it is another type of Mesozoic marine reptile called a mosasaur- Tylosaurus proriger, to be specific.

There were two reasons for this change. First and foremost, I just love mosasaurs- and rest assured, this is not the last time you will see them pop up in my work. They were really cool animals, despite being fairly “normal” as far as marine reptiles go. Unlike plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs and thalattosuchians and all the other marine reptiles, the family that gave rise to mosasaurs is still around today- they’re called monitor lizards. Mosasaurs were literally just monitor lizards that adapted to a fully marine lifestyle. Ron was fully justified to be terror-stricken at the sight of that Australian’s pet goanna! It’s a distant cousin of Tylosaurus!

They were also the undisputed apex predators of the late Cretaceous seas. After springing into being, mosasaurs like Tylosaurus quickly came to dominate the marine reptile guilds of the Western Interior Seaway- the shallow inland sea that covered most of what is today the American Great Plains, bisecting North America in two.

So these guys were really cool, and they would have been a clear threat to humans if they had coexisted with us. Unlike plesiosaurs, which leads me to the second reason for making my animal antagonist a mosasaur.

Most fictional depictions of plesiosaurs are based on now-outdated science. It wasn’t bad science, nor were they bad depictions- we just know more about these animals now than we did before.

So for instance, it is accepted now that that plesiosaur necks were rather stiff and held out straight from the animal’s body. They were biomechanically incapable of lifting their necks out of the water in that elegant, swan-like S-curve, or twisting their necks around like snakes, both of which we see so regularly in fictionalized depictions of them.

They also could not travel on land for any length of time, for the same reason whales cannot- gravity. These were thoroughly marine-adapted creatures; they were not semiaquatic in any way. Penward’s plesiosaur would have been stuck in its pool and of no danger to anyone, unable to act on the fact that park security protocols had failed completely.

This also has implications for cryptozoological accounts of supposed living plesiosaurs, but I will not dwell on those here.

Another problem with plesiosaur antagonists, specifically as it relates to hunting and eating humans, is that not one of them was big enough to actually do this. That we know of, at least- it certainly is possible for there to have been much larger ones, given how patchy the fossil record is4. But as it stands, there is no known plesiosaur whose mouth would have been able open wide enough to swallow a human whole, as depicted by Carnosaur and Lost Tapes. Their skulls were simply too small to swallow such large prey.

It’s now believed that most plesiosaurs preyed on schools of fish and squids smaller than themselves- their conical, interlocking teeth are perfectly adapted to catching fish and preventing them from escaping their mouths, which is horrifying if you are a fish, but not such a big deal if you are a human.

Tylosaurus, on the other hand, absolutely would have been able to kill and eat humans very effectively. We already know they ate human-sized prey- stomach contents from one Tylosaurus specimen included the remains of an 8.2ft Dolichorhynchops, a dolphin-like polycotylid related to the more famous long-necked plesiosaurs. If it was taking those down, a couple of human swimmers would be no issue.

Tylosaurus’s larger cousin Mosasaurus, recently of Jurassic World fame, would have been even more effective at eating humans, but also might have been more likely to ignore us, preferring larger prey like the long-necked plesiosaurs. We’d have been right in Tylosaurus’s preferred prey size-range.

I’m also partial to Tylosaurus due to childhood nostalgia- most of the dinosaur books and shows I viewed as a kid5 depicted Tylosaurus as the apex predator of the Western Interior Seaway, with Mosasaurus being more of a European creature. It wasn’t until just the last few years that I learned Mosasaurus lived in the WIS too, which was simultaneously a cool revelation and a bit of a bummer.

At any rate, I chose my old friend Tylosaurus as the antagonist for the story, and had the time of my life getting incredibly speculative with its intelligence.

Obviously, it isn’t known how smart long-extinct animals were- we can get an inkling at best from looking at endocasts of the brain, brain-body size ratio, and encephalization quotient- but ultimately we have no idea what makes animals intelligent. Even among living animals there are virtually no good metrics to determine what makes one species “smarter” than another, and so it’s totally unknowable among extinct animals.

With such a wide playing field open before me, I opted to give my Tylosaurus cunning on par with that of an orca. This is most apparent with the creature ramming Josie as she is a hairsbreadth from the safety of the beach- orcas in southern Chile really do hunt seals in this manner, deliberately beaching themselves in surprise attacks.

Other aspects of its intelligence were also rooted in orca behavior- for example, spyhopping around the ship to make sure Ron and Josie are still aboard, and its grotesque (from our perspective) play behavior, toying with its victims before killing them. Even attempting to ram the ship into the gully was loosely based on the hunting behavior of orcas washing seals off of pack-ice by swimming towards them at full speed, only to submerge and wait for the seal to get wiped off by the wave they created.

I do not believe mosasaurs really were this intelligent- for one, the intelligence of orcas seems to derive in no small part from their intensely social behavior, whereas the Tylosaurus in the story is solitary, and we have no idea if real ones were or not6- but for storytelling purposes I found it to be within the realm of plausible speculation; after all, there are plenty of intelligent but mostly solitary predators in the world, like tigers.

Addendum: I learned well after publishing this that extant monitor lizards actually do engage in play behavior! At the National Zoo in Washington D.C., one particular female Komodo dragon named Kraken has a well-documented history of playful antics, from pulling on her keepers’ shoelaces and gently pulling objects out of their pockets, to outright playing tug-of-war with them. This is eerily similar to what my Tylosaurus does in the story, and in light of this behavior being present in their closest living relatives, I must amend my perceptions of mosasaur intelligence to- “maybe they really were this smart?”

It certainly made for a terrifying creature. My goal was to have it be a very active antagonist, making the audience wonder what it was going to try next. It knew it had its human prey trapped and was continually plotting ways to get at them.

The appearance of the mosasaur was also almost completely speculative on my part. We know mosasaurs did have tail flukes, due to some amazing fossils preserving the impression of it in the mud the animal died in, but we don’t have the tail fluke of Tylosaurus specifically, so there is some debate about whether it was shaped like an inverted shark’s fin (what I went with) or was more eel-like, or something else entirely. I chose the currently popular interpretation of inverted shark-fin, since that has direct fossil evidence in a close relative, but I do love the more eel-like reconstructions too- indeed, part of me wishes to rewrite it with a more “retro” eel-like tail to fit the old-timey vibe of the story. Whatever fin configuration it had in life, it was still an impressive animal.

The coloration of the animal was speculative, but plausible. For the most part it’s pretty standard for a marine predator- the body is countershaded, with a slate gray back to blend in with the deep dark sea when viewed from above, and a white underbelly to present a less-stark outline when viewed from below against the surface. The stripes on the nose and tail are something of a trope among paleoartists right now; there are plenty of reconstructions depicting them with such, but we have no idea if they really did have such stripes. They look cool though.

The biggest leap of speculation I indulged in was the animal’s eerie eyes- the striking blue with a very diffuse pupil that swirls like ink. I knew Ron was going to look it in the eye and scream at it, and it needed to have the creepiest eyes possible to look back with. The eyes are the windows to the soul, and I wanted these eyes to say- “this animal thinks, but not like you or me”

I looked around at a bunch of extant marine animals- sharks, cetaceans, and the few living marine reptiles we have such as saltwater crocodiles and marine iguanas. Sea kraits in particular had very, very cool looking eyes, and I basically lifted those and gave them to the mosasaur. It’s also possibly plausible? A theory has recently emerged stating that mosasaurs were more closely related to snakes than monitor lizards. I don’t believe this reassessment is accurate, but if true then it wouldn’t be wildly out of bounds for a mosasaur to have eyes like a sea snake.

On the Way to Cape May

As stated, this story was based on the Pensacola sea monster report, which largely revolved around the wreck of the battleship Massachusetts. I’m a strong believer in “creator provincialism”- if a writer grew up in Florida and is steeped in Floridian culture, generally he would do well to set his stories in Florida, because his own experiences with that culture will find their way into the story and contribute to its verisimilitude. I am from Philadelphia and am most familiar with the culture of Pennsylvania and, to a slightly lesser extent, southern New Jersey, so I prefer to set my stories close to home.

Now, unfortunately we don’t live in a Scooby Doo episode and there is a regrettable dearth of large, semi-submerged shipwrecks on which to set such a story. Luckily for me though, there was one perfectly suited to my regional needs. The S.S. Atlantus is a real shipwreck, right off Sunset Beach. She really is made of concrete, and really did run aground just offshore- though a bit closer to the beach than I had her in the story.

The only detail about the ship that I deliberately fudged is the fact that she was scalped of her smokestack in the early 1940s, so Ron and his friends wouldn’t have seen it beckoning to them like a finger. Other than that, the description of the ship is exactly as she looked back then. There are plenty of photos and postcards of her online from back then- today, as stated by Ron, she’s been reduced to little more than a twisted heap of rubble barely poking out of the surf. But back then, you could swim out to her and walk around her decks.

The ship also really did break in two eventually- the two halves are still just barely visible above the waves- so the actions of the Tylosaurus in the story can be taken as an explanation for how that happened in the story’s universe.

I’ve never swam around the wreck- today doing so is extremely dangerous, and not because of any late-surviving mosasaurs- so I don’t know how deep the water actually is there. She ran aground in only about ten feet of water- I added in the deep gully around her to accommodate the forty-foot marine reptile. There probably have been deep gullies near and around her in the past, given the shifting nature of the underwater sands, but this specific one was artistic license on my part.

Cover Art

The cover art for Proriger was a photomanipulation- a real photo of the S.S. Atlantus mixed with a cropped element from Doug Henderson’s painting Asteroid and Leaping Tylosaur- which is my favorite painting of all time. It works… oddly well, I think. It’s obviously not a real photo, the Tylosaurus is clearly illustrated, but it also has this certain look to it where you can almost trick yourself into believing it is real? Maybe it’s just me. I had fun editing it though.

Writing Process

Proriger was one of the most efficiently written stories I’ve ever undertaken. It was an absolute joy to write from start to finish- all the better since I’ve had the idea for the story upstairs for over a year now. I started writing it on January 1, and it took fifteen days from start to finish. I averaged a little over 1,000 words per day on it and never lost that momentum. It was smooth sailing right from the start, which was an immense relief after a disastrous two months of writer’s block.

Right on the heels of my previous story Incarnate, I had planned and started writing an entirely different novelette. It was supposed to be published in late November or early December, alongside another melancholy, autumn-themed vignette collection for November. One thing led to another, and I wound up stalling out on both of these projects. I then fell back to another- coincidentally also Dead Rabbit Radio inspired- story I’d had ready to write for some time… and stalled out on that too. So that was three separate projects I started and then stopped. All of them will be completed at some point- they’re good concepts and I love the ideas… the words just weren’t coming. Which is a shame because Incarnate did so well and then I just went radio silent for two months while stumbling with other projects. Ah well.

Proriger was different. Not once during its writing did I feel frustrated or thwarted by some odd plot snag. The closest I came to this was the decision to cut out one lengthy scene I had written, to improve the flow- since the scene was already written, I published it separately as a kind of “bonus goodie” for anyone interested enough to check it out. Other than this… it was just very straightforward to write. I mean it’s a straightforward story- kids go out to a boat, get eaten by a monster. Not much to mull over.

It also helped immensely that it was a first-person narrative. Readers are free to disagree, but I feel like first-person stories don't have to be as neatly polished as third-person ones. It’s a looser form than third person. With third person, you’re essentially assuming a God’s eye view of the story, so there is a greater duty incumbent upon the writer to describe things accurately and poetically. First person, meanwhile, is just somebody talking, conversationally- you can use slang, you can be a bit messier with descriptions. So the editing process for Proriger wasn’t nearly as arduous as editing, for instance, The Veldt, even though the latter was a shorter story.

Building off of this comparison with my earlier longform work, Proriger also didn’t have many deep thematic elements like The Veldt, or Stheno, or Perihelion. Those stories are teeming with metaphors and allegories. Proriger is just a straightforward monster story. The main “message” is one it shares with all other tales of its kind- don’t go swimming at night in places you’re not supposed to be.

I hope- for those of you who made it this far- that this wasn’t too boring a read, or that it felt overly indulgent. I always enjoy when other writers and artists discuss their own techniques and inspirations, so I figure there’s a small chance you guys might enjoy hearing a bit about mine.

That’s all. You can go home now.

But they were not, as many continue to mistakenly believe, dinosaurs themselves!

Parenthetically, it is not a coincidence that most of the fiction about plesiosaurs is cryptozoological in nature. The idea of a late-surviving dinosaur-adjacent creature hiding in the lake is just cool, of course people would write about it!

This book was written six years before Jurassic Park, by the way- the similarities are entirely coincidental.

The fossil record for ichthyosaurs keeps revealing there to have been true giants among them, and we will probably soon come to find that they grew larger than blue whales.

On the TV front, the documentaries Chased By Sea Monsters and Sea Monsters: A Prehistoric Adventure were particularly formative.

Given the presence of bite marks on the skulls of many Tylosaurus specimens which were plainly inflicted by other tylosaurs, and at least one specimen which was killed by a conspecific, it seems like they weren’t extremely social like cetaceans.